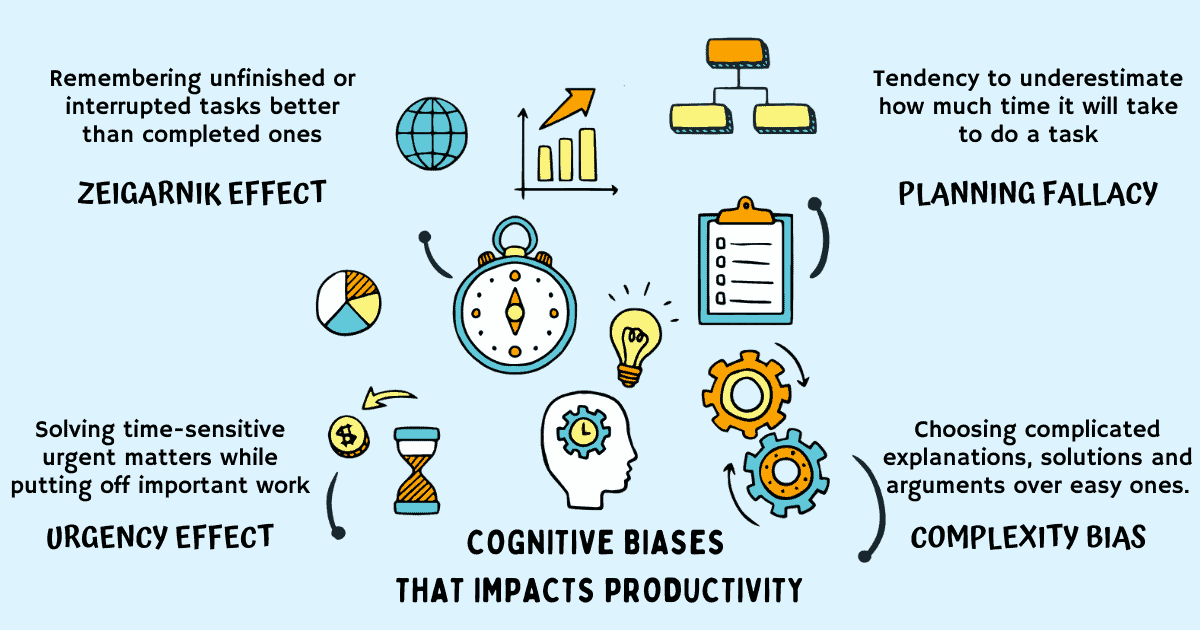

4 Cognitive Biases That Impacts Productivity

I have always been very conscious about how and where I spend my time. While I paid a lot of attention to the obvious ways to be more productive—create a distraction free focused zone, limit time on social media, divide my work into small blocks of time, take regular breaks to revive and rejuvenate—I missed a crucial element that often gets in the way of our productivity.

Our brain.

The human brain has this remarkable cognitive capacity to perform at levels far beyond what we consider as our natural abilities, but it’s not without its limits. The cognitive biases that enable the brain to prioritize and process large amounts of information quickly also gets in the way of our productivity. These mental shortcuts are the brain’s way to conserve energy and work more efficiently. But they also lead to many thinking errors.

Here are the 4 cognitive biases that have the biggest impact on our productivity—how we prioritize, make decisions, manage time and get work done.

- Urgency effect

- Zeigarnik effect

- Complexity bias

- Planning fallacy

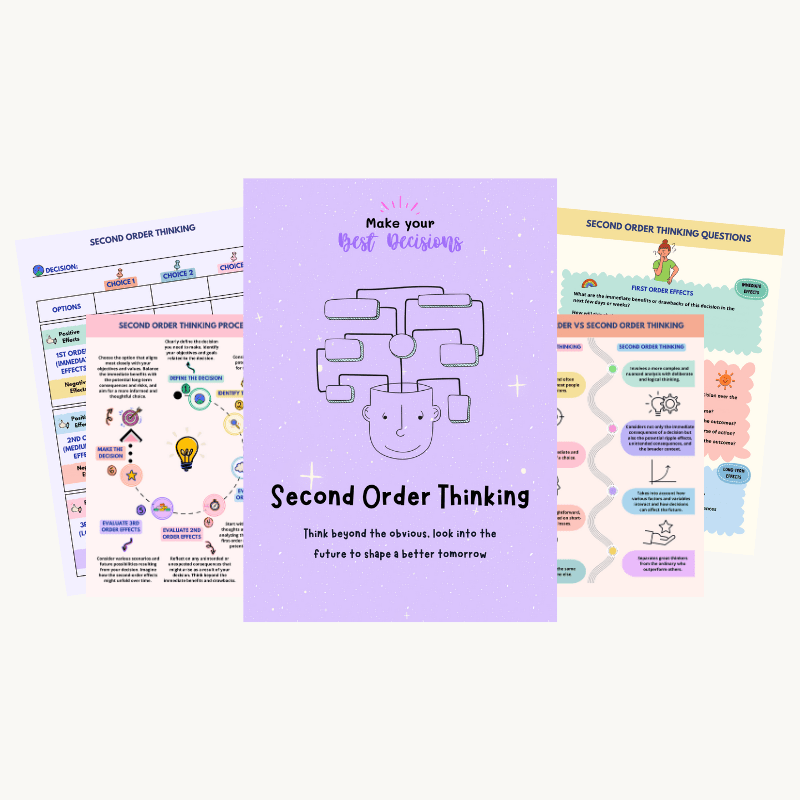

Cognitive Distortions Bundle

Challenge and replace irrational thoughts with more realistic and adaptive thoughts.

Urgency effect

When an urgent task comes knocking at the door, do you push important work aside because urgent tasks demand your immediate attention while important goals are far off into the future and can wait until later?

Urgency effect makes us jump at every chance to solve time-sensitive urgent matters while putting off important work. Rationally our brain knows that important tasks have a larger payoff and bigger rewards in the long run, but under the effect of this bias, we fall victim to perceiving urgent as important.

Urgent tasks keep us busy and make us feel important, but they also suck into our time. Prioritizing it at the expense of more impactful work keeps us trapped into an illusion of productivity.

Why we fall for urgency effect

Important tasks typically have no specific deadline. They are time consuming and complex as they often require looking into the future and proactively identifying its needs. Giving clarity to vague ideas, making crucial decisions or laying out a future strategy is not only time consuming, it’s also mentally taxing.

Urgent tasks have easy to reach, visible goals. They bring instant gratification with a big hit of dopamine. Since dopamine serves as a reinforcement for remembering and repeating pleasurable experiences, you end up dedicating more time to urgent tasks at the expense of more impactful work.

Continuously pushing important tasks to the back burner keeps us locked in a never ending cycle of unproductive choices—dedicating less time to important work inevitably creates more urgency later. Important tasks become urgent in due course of time if delayed too much, not given proper attention or carried out without real interest.

Example of urgency effect

Gina is the tech manager of the CRM team. The latest releases in ChatGPT and other AI innovations is becoming a threat to her business. But instead of spending time planning how to make them a part of their future strategy, Gina ends up spending most of her time on emails, meetings and other urgent tasks. Her busyness keeps her locked in a cycle of unproductivity and inefficiency.

Urgency effect makes her pay more attention to the work right in front of her—emails, chat notifications, customer escalations—while pushing important work aside.

How to avoid urgency effect

A great practice to avoid urgency bias involves using The Eisenhower Matrix for prioritization. To put the Eisenhower matrix to use, go through each task one by one and separate them into four possibilities:

- Important and Urgent (Quadrant 1): reduce time spent here

- Important and Not Urgent (Quadrant 2): consciously prioritize and schedule these tasks

- Not Important and Urgent (Quadrant 3): delegate these tasks

- Not Important and Not Urgent (Quadrant 4): declutter and eliminate.

Eisenhower Productivity Planner Worksheet

Organize your to-dos and clear out unnecessary tasks with the help of this powerful planner.

Consciously scheduling dedicated hours on the calendar to do important work makes it more likely that you attend to them without interruptions. A few other practices to adopt:

- Set aside specific blocks of time for responding to emails, chats or other such tasks.

- Reduce time spent in meetings.

- Utilize your peak productivity period to do your most important work. Matching your energy with the physical and mental demands of work will enable you to do your best work making it more likely for you to continue instead of giving up.

- Set deadlines for important tasks and hold yourself accountable to meeting them.

Zeigarnik effect

Thoughts of unfinished tasks keep popping up in our head right when we get down to work or are trying hard to focus.

Emails we haven’t replied to.

Pending design to compete.

Meetings to schedule.

… so on and on.

These intrusive thoughts that take away our attention even for a split second makes it hard to concentrate and get any meaningful work done. Distractions from incomplete work prevents us from entering into a state of flow—which is when we are completely immersed in a task and the time seems to stand still. Flow minimizes distractions, prevents procrastination and leads to high performance and productivity.

Named after psychologist Zeigarnik who first discovered it, the effect refers to the tendency to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. Letting our brain continually remind us that we haven’t done something is quite unpleasant and it can even lead to stress, anxiety and burnout.

Why we fall for Zeigarnik effect

Zeigarnik and her professor Kurt Lewin observed that their restaurant waiters remembered everyone’s orders despite never writing anything down. But as soon as the bill was paid, they had little or no memory of who their customers were or what they had ordered.

This led to a series of experiments based on which Zeigarnik concluded that human minds treat tasks that have been completed differently from those that are still left to complete. A task that has already been started establishes a task-specific tension, which keeps it at the forefront of our memory. The tension is relieved upon completion of the task, but persists if it is interrupted or not yet complete.

That’s why unfinished tasks keep coming back to haunt us. Look another way, these reminders can actually be useful to help us finish incomplete projects only if they do not spoil our attention right in the middle of another project.

Attention is like energy in that without it no work can be done, and in doing work is dissipated. We create ourselves by how we use this energy. Memories, thoughts and feelings are all shaped by how we use it. And it is an energy under control, to do with as we please; hence attention is our most important tool in the task of improving the quality of experience.

― Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow

Example of Zeigarnik effect

Zeigarnik effect is used in gamification:

- Progress trackers which inform users of how close they are to complete a task. For example, when users see a message like “Your profile is 34% complete”, they are more likely to spend a few minutes on providing all missing details. This technique is used by LinkedIn to collect user information in a super smart way.

- Checklists that provide users a clear step-by-step flow to onboard users faster and effectively.

- Interrupted commercials are more likely to be remembered than those which are not due to the Zeigarnik effect. Advertisers use it to catch the attention and memory of viewers.

How to avoid Zeigarnik effect

Research by Florida State University shows that planning work upfront and writing it down can free your mind from distracting thoughts about unfinished work. Have daily, weekly and monthly rituals to review, prioritize and plan what you intend to do. When you miss something and it pops up in your head, don’t leave it hanging there, immediately write it down.

Daily Weekly Monthly Planner Worksheets

Manage your to-do list, stay productive and cultivate healthy life habits with these planners.

Moving tasks from your head onto paper relaxes your brain and helps you focus on the task at hand. A few other practices to adopt:

- Avoid procrastination by using the Zeigarnik effect to your advantage. Instead of putting things off because they are big or complex, simply take a very small step towards it. Once you get started, your brain will kick off the Zeigarnik effect enabling you to keep going till the end.

- Use the Pomodoro method to divide your work into small chunks of focused time. The tactical breaks in the Pomodoro method improves memory and keeps productive momentum going.

Complexity bias

Given a choice between two competing solutions, we are likely to choose the more complex one.

Jargons catch our attention over simple explanations.

Difficult to execute strategies impress us over straightforward ones.

Sophisticated products appear more authoritative while the ordinary ones appear inferior.

But complexity has many problems.

- Knowing upfront that something is difficult can prevent us from getting started.

- Obstacles and challenges along the way make it hard to persist and we may give up too soon.

- It can delay decision making.

- It’s costly as it requires more time, effort and resources to get done.

- It can be potentially dangerous. Not understanding something fully can lead to wrong assumptions and conclusions. It can lead to hiding mistakes and fundamental flaws.

Complexity bias is this tendency to prefer complicated explanations, solutions and arguments over easy ones.

Why we fall for complexity bias

Many people mistake simple for easy. Finding simple solutions to problems may sometimes require more effort—conscious effort to dig deeper and give way to our creative mind, avoiding biases to cut through complexity and finding solutions that do not require too much scaffolding to support.

Complexity in such cases could be an excuse to label the problem as too confusing and shove it aside.

We choose complexity over simplicity for another reason: it’s falsely associated with expertise, innovation and authority. The more complex or advanced the approach is, the more superior it appears. Put another way, if a solution is too simple, we assume it won’t solve the problem.

This makes us inject complexity and over complicate things instead of choosing a simpler approach.

As Edsger Wybe Dijkstra, a Dutch computer scientist once said “Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.”

Example of complexity bias

Jim got an opportunity to prepare and present the design of a new product to his entire team. He wanted the solution to stand out and establish credibility with others.

But instead of asking the question “What problem is this product required to solve and how can I solve it in the simplest way possible?” he asked “What problem is this product required to solve and how can I make it look good?”

Trying to make the solution appealing led to poor choices:

- Instead of choosing a simple technology he understood well, he decided to use a new technology with no experience or expertise.

- He made complex architecture decisions to make the product look sophisticated.

- He introduced features that added little to no value to a customer but sounded interesting to implement.

Complexity bias in his case led to poor decisions and terrible choices.

How to avoid complexity bias

To counteract complexity bias, apply Occam’s razor. It is one of the most useful mental models to solve problems. Occam’s razor advocates simplicity by focusing on key elements of the problem, eliminating improbable options and finding solutions with less assumptions.

Another useful mental model to reduce complexity is first principles thinking. It requires breaking down a problem into its fundamental building blocks (its essential elements), asking powerful questions, getting down to the basic truth, separating facts from assumptions and then constructing a view from the ground up.

Mind Map Templates

Work through complex problems, identify correlations, and see the big picture using these mind map worksheets.

A few other practices to adopt:

- Since complexity bias shields you from seeking simple solutions, asking for others’ opinions may be helpful. You may ask “Is my solution too complex or confusing?”

- Question your intent. Reframe the end goal to align it with the outcomes you wish to achieve.

- Show bias for action. Instead of being stuck in analysis paralysis, take a small step towards your goal, see how it works and slowly improve it over time.

Planning fallacy

When it comes to setting deadlines, most of us are highly optimistic. Even if it’s something similar to what we have done in the past, we are still likely to underestimate how much time it will take to do it in the future.

It took one week to finish a design proposal last time, but if you have to do it again, you’re positive it will get done in less than a week.

It took more than a month for your new hires to get onboarded last time, but while planning for the new batch coming in next week, you allocate only 2 weeks.

Planning fallacy is what makes us commit to overly optimistic timelines, miss those deadlines and then drown in guilt, anxiety and stress. Not factoring in realistic demands of the task leads to poor planning for the future. It harms your reputation and also breaks trust because when you miss those deadlines, others assume that you don’t take your commitments seriously.

Why we fall for planning fallacy

When estimating the time it will take to complete a specific task, we ignore risks and other unlikely events that may prevent us from completing the task on time.

Taking the best case scenario into account and ignoring the obstacles we might encounter along the way leads to wishful thinking. We have the best intentions to get the work done quickly and efficiently, but good intentions aren’t always enough. Good planning needs good estimation skills.

Another reason why we are highly optimistic about completing a specific job is our tendency to get stuck in the nitty gritties while ignoring the big picture. Not taking the big picture into account leads to poor estimation—we make wrong assumptions and ignore the time it will take to integrate our work into the bigger picture.

We are also really bad at accurately judging our own skills and abilities. Our enthusiasm to meet our goals adds to the planning fallacy.

Worst part? We don’t even learn from our past mistakes. Even when we are able to recognize past mistakes when we were overly optimistic, we keep on making the same mistakes in the future.

We focus on our goal, anchor on our plan, and neglect relevant base rates, exposing ourselves to the planning fallacy. We focus on what we want to do and can do, neglecting the plans and skills of others. Both in explaining the past and in predicting the future, we focus on the causal role of skill and neglect the role of luck. We are therefore prone to an illusion of control. We focus on what we know and neglect what we do not know, which makes us overly confident in our beliefs.

― Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

Example of planning fallacy

Tina is working on the estimates of a new product. She has worked on a similar product in the past. Last time she built the product, it took her 3 months to complete. The project was initially estimated for 2 months but took an additional month due to requirements change, longer testing cycle and other unforeseen issues.

Tina has experience from the past that she should put to use to determine how long it will take to complete the current project. However, due to the planning fallacy, she commits to a 2 month deadline again. She justifies it by assuming that her experience from the past project will help her finish the tasks sooner while completely disregarding the additional time it will take to handle unexpected issues.

How to avoid planning fallacy

Break down the project into small parts and estimate how long each one will take. Doing this work upfront will make your effort estimates much closer to reality than being vaguely guided by hunch.

Another great strategy is the one recommended by Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow. He suggests taking an outside view of your estimates by consulting others—asking questions and identifying problems and mistakes they made on similar projects in the past. You can’t do this for all your tasks, but definitely do it for your most crucial ones.

Irrespective of how good you’re at estimation, some unlikely event can crop up and make your project fall through the cracks. It isn’t possible to take every such scenario into account and plan for it. But what’s possible is to add a little buffer to your estimates—add 20% breathing room while considering the effort it takes to do something.

Finally, and this is the most important one: implement a feedback loop in your process. Track your time. Make a note of how long it takes to do something. When you miss deadlines, identify what mistakes you made and what changes you need in your planning process to do better next time.

Amazing Goal Planner

Become your best self by setting and achieving goals in all important areas of your life.

When you’re conscious of how these biases—urgency effect, Zeigarnik effect, complexity bias and planning fallacy affect your time and apply the right strategies to overcome them, you can be your most productive self.

Summary

- Most of us struggle with getting work done efficiently because we don’t pay attention to the cognitive biases that get in the way of using time productively.

- Urgency effect makes us waste time attending to urgent tasks at the cost of important tasks. Not paying attention to the future needs keeps us trapped in a cycle of unproductivity.

- The Zeigarnik effect prevents us from giving our best to the task at hand. When our mind keeps reminding us of incomplete or interrupted tasks, it’s hard to stay focused and pay attention.

- Complexity bias makes us add unnecessary complexity to solutions which increases the time, effort and cost to solve even simple problems.

- Planning fallacy tricks our mind to give highly optimistic estimates to achieve a certain goal despite our previous experience telling us that it will be impossible to achieve it.