Strategies For Learning From Mistakes: How To Beat Self Justification And Think Clearly

We are programmed at an early age to think that mistakes are bad. Don’t make a mistake, you won’t get good grades. Choose the right career, there’s no going back. Make up your mind, there won’t be a second chance. You will regret this decision later. What were you really thinking? All this well-meaning advice rings loud and clear in our heads, conveying a simple message – stay away from mistakes.

Living in a mistake-phobic culture that links mistakes with stupidity and incompetence, it isn’t easy to admit a mistake. While most of the decisions we make aren’t about life and death and the consequences are rather trivial, we find it extremely hard to say “I made a mistake.” We avoid taking responsibility for our actions and use blame, lies and other fanciful stories to avoid looking like an idiot.

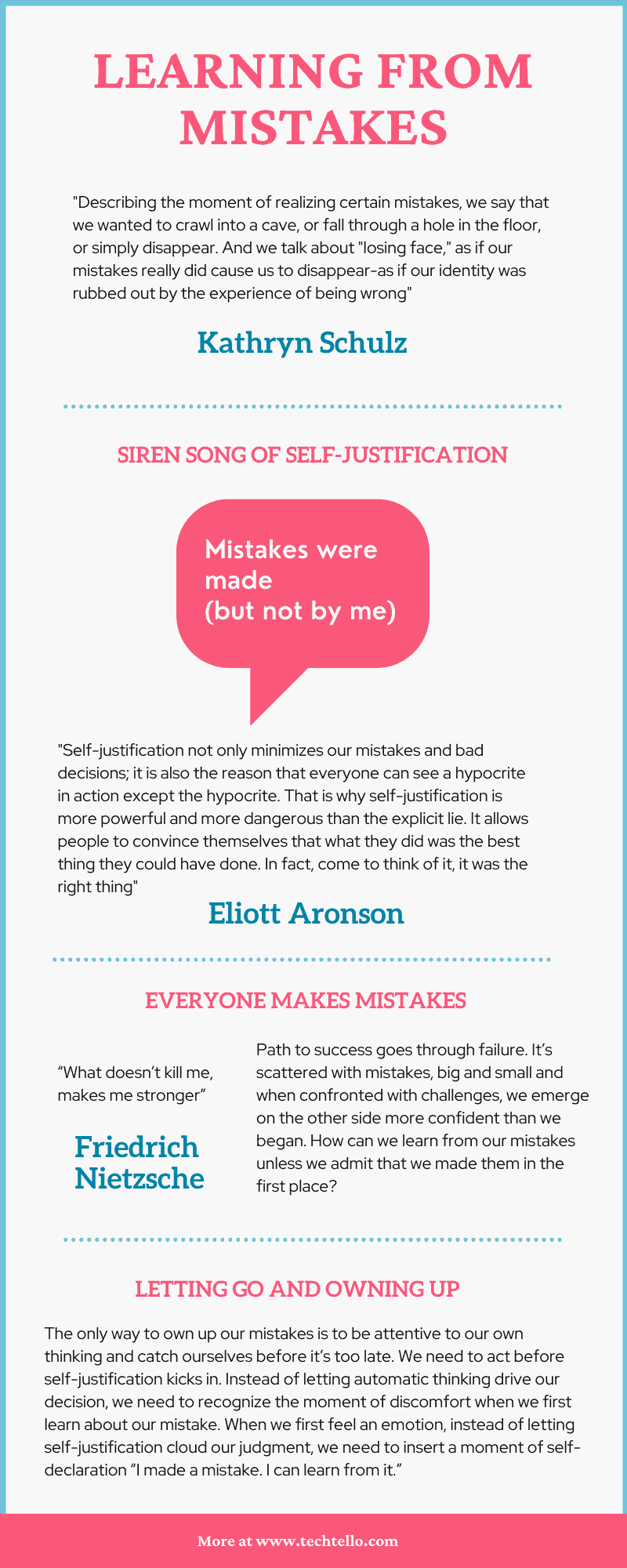

So extreme is our reaction to mistakes that we wish ourselves out of existence, says Kathryn Schulz in Being Wrong. She adds “Describing the moment of realizing certain mistakes, we say that we wanted to crawl into a cave, or fall through a hole in the floor, or simply disappear. And we talk about “losing face,” as if our mistakes really did cause us to disappear-as if our identity was rubbed out by the experience of being wrong.”

This thinking gets reinforced once we join a workforce. We soon realize that people don’t encourage open discussions, ask questions or use humility and curiosity to get to the underlying root cause, rather blame gets in the way of embracing failure lessons. We notice that no one practices openness or has patience and tolerance for mistakes. We adapt to a work culture where admitting mistakes becomes synonymous with taking the blame.

The mental energy best put to use in solving problems is spent in avoiding mistakes or covering them up once they do happen. What mistake! I didn’t make a mistake! I did my best! It wasn’t simply possible! It was the right thing to do! Covering up mistakes instead of owning them leads to a rift between couples, loss of trust between friends, unhealthy practices at work and it even stalls our own personal growth.

Friedrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher once stated “What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger.” It conveys a simple fact – the path to success goes through failure. It’s scattered with mistakes, big and small and when confronted with challenges, we emerge on the other side more confident than we began. How can we learn from our mistakes unless we admit that we made them in the first place?

But it’s not as easy as it sounds. Acknowledging a mistake is simply an acknowledgment of its existence, accepting our part in it is an altogether different story. Even if we seem open to the idea of learning from our mistakes, self-justification can get in the way.

Siren song of self-justification

Most of us think of learning from mistakes as a three-step process:

- Acknowledge the mistake

- Reflect on what went wrong and assimilate it into easy-to-implement strategies

- Put these strategies to action

Easy peasy lemon squeezy. Not so much. It’s more complicated than that. Usually, when we make a mistake, we feel an emotion – anger, sadness, disappointment, frustration, hopelessness, anxiety, fear, or embarrassment, and then we try to rationalize that emotion. We give it a language by telling ourselves a story. It’s at this stage that reality goes up for distortion as self-justification kicks in. And self-justification is really good at its job. It won’t budge once you let it in by ignoring any outside information that interferes with its own conclusion.

Self-justification is the lie we tell ourselves, says Elliot Aronson, a psychologist who has carried out multiple experiments on the theory of cognitive dissonance, in Mistakes were made (but not by me). He explains “Self-justification not only minimizes our mistakes and bad decisions; it is also the reason that everyone can see a hypocrite in action except the hypocrite. That is why self-justification is more powerful and more dangerous than the explicit lie. It allows people to convince themselves that what they did was the best thing they could have done. In fact, come to think of it, it was the right thing.”

Since self-justification works beneath consciousness, we do not even realize that it’s protecting us by acting as a shield and shunning away our responsibility. It feeds our mind with alternative theories to describe our experience, one where we aren’t responsible for the mistake.

Mistake: Couldn’t finish the project on time.

Self-justification: The product team didn’t provide the requirements clearly.

Mistake: Forgot to call mom on her birthday.

Self-justification: It’s not that big a deal. She doesn’t even remember her own birthday.

Mistake: Lost a major deal.

Self-justification: What a stupid bunch. They can’t even see their own loss. Good, this didn’t work out. I can now spend my energy with people who are worth my time.

Mistake: A marketing strategy that failed and costed the company a lot of money.

Self-justification: It indeed was a great strategy. No one could have anticipated the shift in market demand. We at least survived. Look at others who couldn’t keep up with this change.

With self-justification by our side, the courage to accept the reality of our situation and the humility to do the right thing never even crosses our minds. After all, we don’t know what we don’t know. We are oblivious to self-justification. Think about some of your mistakes in the past – did you do the right thing or took the best possible action? Since we don’t question our own thinking, how can we ever catch our flawed justification.

Elliot Aronson explains how over time as the self-serving distortions of memory kick in, we forget or distort past events and come to believe our own lies, little by little. He adds “We know we did something wrong, but gradually we begin to think it wasn’t all our fault, and after all the situation was complex. We start underestimating our own responsibility, whittling away at it until it is a mere shadow of its former hulking self. Before long, we have persuaded ourselves, believing privately what we originally said publicly.”

Everyone makes mistakes

N. Wayne Hale Jr. was launch integration manager at NASA in 2003, when seven astronauts died in the explosion of the space shuttle Columbia. In a letter to NASA employees, Hale took full responsibility for the disaster. He accepted his mistake:

“I had the opportunity and the information and I failed to make use of it. I don’t know what an inquest or a court of law would say, but I stand condemned in the court of my own conscience to be guilty of not preventing the Columbia disaster. We could discuss the particulars: inattention, incompetence, distraction, lack of conviction, lack of understanding, a lack of backbone, laziness. The bottom line is that I failed to understand what I was being told; I failed to stand up and be counted. Therefore look no further; I am guilty of allowing Columbia to crash.”

Even though a worker at Kennedy Space Center had complained to him that they hadn’t heard any NASA managers admit to being at fault for the disaster, he said “I cannot speak for others but let me set my record straight. I am at fault.”

He wrote in his letter “the nation has told us to get up, fix our shortcomings, fly again — and make sure it doesn’t happen again. … The nation is giving us another chance. Not just to fly the shuttle again, but to continue to explore the universe in our generation.”

This NPR article describes how he solved the cultural problems at NASA. He said, “The first thing we’ve got to do is we’ve got to put the arrogance aside.” He became a listener. When an engineer came to him with an issue after the accident, even if he didn’t understand it, he tried. Hale oversaw many of the shuttle flights after the accident. It did not fail again. He says they made plenty of changes to checklists. But he thinks the biggest change was that everyone who worked at NASA became better at talking — and listening. That’s the power of acknowledging mistakes and learning from them.

In another astonishing event, Oprah Winfrey dedicated an entire show apologizing for making a mistake. This is how the story goes.

A Million Little Pieces, published in 2003 was James Frey’s memoir of drug addiction and recovery. Oprah Winfrey picked up the book for her popular on-air book club, an endorsement that boosted Frey’s sales into millions as his memoir climbed the best sellers list.

Later in October 2005, Frey appeared on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” to promote his book, which Oprah had previously said she “couldn’t put down,” calling it “a gut-wrenching memoir that is raw and it’s so real.” Then on January 8, 2006, The Smoking Gun website published that Frey had falsified and exaggerated many parts of his story. At first, Oprah justified her support for Frey when she called the “Larry King Live” show and said, “The underlying message of redemption in James Frey’s memoir still resonates with me and I know that it resonates with millions of other people who have read this book, and will continue to read this book.”

But later Oprah realized her mistake and took responsibility for it. She got Frey onto her show once again and started right off with an apology for her call to Larry King Live show “I regret that phone call,” she said to her audience. “I made a mistake and I left the impression that the truth does not matter and I am deeply sorry about that because that is not what I believe. I called in because I love the message of this book and at the time and every day I was reading e-mail after e-mail from so many people who have been inspired by it. And, I have to say that I allowed that to cloud my judgment. And so to everyone who has challenged me on this issue of truth, you are absolutely right.”

Later in the show, she even told Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen who had called Oprah “not only wrong, but deluded” that she was impressed with what he said, because “sometimes criticism can be very helpful. So thank you very much. You were right. I was wrong.” Towards the end of the hour, the New York Times columnist Frank Rich appeared on the show to echo Richard Cohen, giving kudos to Oprah for speaking up, for taking a stand. “The hardest thing to do is admit a mistake,” he said.

If Oprah and Hale could acknowledge their mistakes in front of millions of people, why can’t we do it too? Mistakes are not terrible personal failings that need to be denied or justified, they are inevitable aspects of life that can help us grow.

Letting go and owning up

“People make mistakes all the time,” says Ryan Holiday in Ego Is The Enemy. He adds “They start companies they think they can manage. They have grand and bold visions that were a little too grandiose. This is all perfectly fine; it’s what being an entrepreneur or a creative or even a business executive is about. We take risks. We mess up. The problem is that when we get our identity tied up in our work, we worry that any kind of failure will then say something bad about us as a person. It’s a fear of taking responsibility, of admitting that we might have messed up. It’s the sunk cost fallacy. And so we throw good money and good life after bad and end up making everything so much worse.”

Does this attitude lead to great things? Absolutely not. What does – letting go, owning up and moving on.

The only way to own up our mistakes is to be attentive to our own thinking and catch ourselves before it’s too late. We need to act before self-justification kicks in. Instead of letting automatic thinking drive our decision, we need to recognize the moment of discomfort when we first learn about our mistake. When we first feel an emotion, instead of letting self-justification cloud our judgment, we need to insert a moment of self-declaration “I made a mistake. I can learn from it.”

By saying this out loud multiple times, we can empower our mind to adopt a solutioning mode instead of adopting a self-defeating goal of pushing blame externally. We can choose a different experience, one in which we no longer hide behind our mistakes, look to them as a measure of our competence or feel robbed of our identity because of them.

We can adopt the mindset of a learner by considering our mistakes as a learning experience, a teaching moment on how our behaviours and actions define our future, an acceptance that mistakes are a necessary part of building new skills and acquiring new knowledge or as Adam Grant says in Think Again “Being wrong won’t always be joyful. The path to embracing mistakes is full of painful moments, and we handle those moments better when we remember they’re essential for progress. But if we can’t learn to find occasional glee in discovering we were wrong, it will be awfully hard to get anything right.”

Once we acknowledge our mistake, analyzing it is the next difficult step. It’s easy to get carried away by emotions and speed through the analysis by attaching superficial reasons or drawing insignificant conclusions. Don’t fall for it. You can’t really learn from your mistake unless you move from addressing the symptom to exploring the root cause. Fix the symptom and you will find yourself repeating this process quite often. Fix the root cause, and there, you have stopped the mistake from happening again saving yourself time and energy to do the real work.

A great technique to identify the root cause is five-whys technique designed by Sakichi Toyoda who used it within Toyota Motor Corporation during the evolution of its manufacturing methodologies. It goes like this – Ask why the mistake occurred and use the response from the first question as the basis for the next question. Repeat this process (5 is a general recommendation, you can stop at 3 or keep going) unless you have the answer that seems right. Let’s take this example:

- Q: “Why did I miss the meeting yesterday?” A: I slept till late in the morning.

- Q: “Why did I sleep till late in the morning?” A: I was working till late the previous night.

- Q: “Why was I working till late the previous night?” A: I am running behind an upcoming deadline and need to catch up on my work.

- Q: “Why am I running behind on my deadline?” A: I did the wrong effort estimation.

- Q: “Why did I do the wrong effort estimation?” A: I did not spend time in analyzing the complexity of the problem and was overconfident in my abilities.

This example is a clear demonstration of how the original answer to the mistake differs greatly from the actual source of the problem. Unless time is invested in solving the estimation problem, more such mistakes will keep cropping up.

Now that you know how useful mistakes are, let go of the burden of covering up your mistakes and take pleasure in owning them. Even if you have been told throughout your life that “mistakes are bad” and the culture around you still supports the belief, you can choose to opt-out of it. You can stand apart and be an outlier. Through your actions, you can encourage others to rethink their conclusions too. Isn’t that worth a try?

Ending with these thoughts from Ben Horowitz as stated in this article “All the mental energy that you use to elaborate your misery would be far better used trying to find the one, seemingly impossible way out of your current mess. It’s best to spend zero time on what you could have done and all of your time on what you might do. Because in the end, nobody cares.