Confirmation Bias: Going Beyond Our Personal Narrative

We gravitate towards people who are like us and will most likely believe what we believe. Doesn’t it feel good when others conform to our ideas? Who likes being told that they are not right or what they believe is far from reality?

The desire to be right crushes the intent to find the objective truth – being wrong is considered bad, criticism is viewed as an attack on our personality and disagreements are regarded as time-wasting activities that do not add value.

When confronted with information that challenges our personal narrative, we consider the other person as either ignorant, evil or outright stupid. Instead of being curious about the new information and using that to update our beliefs, we work hard and find ways to reject the evidence that contradicts our beliefs and look for information that strengthens our point of view.

Interpreting and selectively gathering data to fit our beliefs as opposed to using opposing views to update our mental models is a cognitive bias known as confirmation bias that’s part of being human. It is how our brain has evolved to think fast, process information and act automatically all without any role from our conscious mind.

From an evolutionary perspective, much of the automatic processing by our brain happens in the older parts of our brain like basal ganglia, amygdala and other brain regions, while the deliberate thinking that requires conscious effort, choice and concentration happens in the prefrontal cortex.

This capacity of our brain to run on autopilot is tremendously useful to our day-to-day function and forms a large part of what we do. So, while we should not make an attempt to change our brain, we can definitely learn to work within its limitations by being aware of our biases and taking conscious steps to overcome them.

How can we recognize confirmation bias?

Driven by the need to act fast, make decisions with incomplete information, deal with information overload while trying to make sense of it, cognitive dissonance springs our reflexive system to action and applies shortcuts without our conscious awareness.

For a long time, I thought smart and open-minded people must be shielded from this bias. Well, I was wrong. Multiple scientific studies show that smart people are more prone to confirmation bias as it’s easy for them to rationalise their own line of thinking and dig up information that supports their belief.

Daniel Kahneman describes this in his book Thinking, Fast And Slow

As we navigate our lives, we normally allow ourselves to be guided by impressions and feelings, and the confidence we have in our intuitive beliefs and preferences is usually justified. But not always. We are often confident even when we are wrong, and an objective observer is more likely to detect our errors than we are

To recognise confirmation bias, ask yourself these 3 questions:

1. What information do you remember

We rely on our past experience to guide our future decisions. All past experiences have an element of the good and the bad, instances that confirmed our beliefs and moments where they were challenged, outcomes that aligned with our expectations and results that disappointed us.

When drawing on past memories to steer you in the right direction, what kind of information do you remember

- Decisions where others supported your viewpoint or raised counter arguments

- Information that strengthened your beliefs or challenged it

- Positive results that were in line with your decision or failed to generate the desired impact

If all that comes to mind is information that justifies your current decision without arguments that contradicts it, you are selectively choosing to remember details that validates your point of view.

This is confirmation bias in action.

2. What evidence do you seek

How you seek new information also plays a big role in whether you are looking to rationalise your point of view or want to genuinely acquire knowledge by examining alternate hypotheses

- Do you encourage dissent or agreement

- Do people around you always agree with you leading to groupthink or feel comfortable to bring out a different perspective

- How do you react to information that goes against your initial position

- Do you reward ideas that are in line with your belief system or inspire diverse thinking

If your behaviour and actions reflect confirmatory style as opposed to exploratory style, you act out of confirmation bias.

Cognitive Distortions Bundle

Challenge and replace irrational thoughts with more realistic and adaptive thoughts.

3. How do you interpret data

When dealing with incomplete or unclear information, do you fill in the missing information with your interpretation of the gaps? How do you choose to manipulate data?

- Do you examine data that validates your thinking or counters it

- Do you see both sides of the data without initial judgement and opinion

- Are gaps in information substituted with your knowledge without check for fallibility

Looking at the data that conforms with your original line of thinking may give you the confidence in your decision, but without calibrating the other side of this data, you cannot draw a correct inference. Rather, you are simply giving in to confirmation bias and twisting the data in your favour.

As Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist and Wharton professor said “If there’s no data contradicting your viewpoint, you haven’t looked hard enough”

Why our brains are wired for confirmation bias

We seem to have two brains – one that is fast, instinctive, reactive, emotional and automatic and another that is slow, deliberative, logical and lazy.

Daniel Kahneman is a psychologist and economist notable for his work on the psychology of judgement and decision-making, as well as behavioural economics, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. In his classic book Thinking, Fast and Slow he refers to these two brains as two systems – system1 and system2.

System1 drives most of our daily decisions that make it possible for us to live a large part of our life without any effort and keeps us alive. It’s what helps us perceive the world around us, form connections and draw new associations between ideas. Applying brakes when we sense danger while driving, turning back when we hear a loud noise, walking down to the nearby grocery store to fetch supplies, eating our meals all seem to come naturally to us.

Once we learn new things, it becomes an automatic part of what we do and how we do certain things. All our routine activities are guided by system1 without our conscious awareness. Due to the complexity of the world and vast amounts of information in it, system1 simplifies inputs and applies shortcuts to enable itself to act fast. System2 is invoked only when system1 needs help and doesn’t know what to do in a certain situation.

Psychological attack triggers the same part of the brain as a physical threat. When others oppose our ideas and beliefs or we come across information that counters our decision, it’s perceived as a threat by our brain which triggers system1 to act fast with the intent to protect. Without our system2 being aware, system1 may decide to lean towards people or ideas that support our beliefs as opposed to those who contradict it. This fight or flight response from system1 without our awareness gives way to confirmation bias.

Since system1 is highly useful and practical in guiding most of our decisions and helping us live our life, we cannot get rid of it. It won’t make sense to invoke system2 for all our decisions as it is much too slow and lazy to guide our day-to-day decisions.

Mind Map Templates

Work through complex problems, identify correlations, and see the big picture using these mind map worksheets.

When do we need to use our critical thinking skills

It’s important to recognise and take charge of decisions which may have a large impact on our future. New and unfamiliar situations, incomplete information, being surrounded by like-minded people and culture where dissent is discouraged are all prone to confirmation bias.

Daniel Kahneman explains when to use critical thinking skills in his book Thinking, Fast And Slow

System 1 operates automatically and cannot be turned off at will, errors of intuitive thought are often difficult to prevent. Biases cannot always be avoided, because System 2 may have no clue to the error. Even when cues to likely errors are available, errors can be prevented only by the enhanced monitoring and effortful activity of System 2. As a way to live your life, however, continuous vigilance is not necessarily good, and it is certainly impractical. Constantly questioning our own thinking would be impossibly tedious, and System 2 is much too slow and inefficient to serve as a substitute for System 1 in making routine decisions. The best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognize situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high

Unless we learn to recognise situations in which to invoke our deliberative mode of thinking and make a conscious effort to combat confirmation bias, we may make decisions with biased opinions, incomplete information and subjective truth with higher chances of failure.

5 strategies to combat confirmation bias

Learning limitations of our brain is critical to devising strategies to combat confirmation bias. Without this knowledge, our mind can trick us into believing we are not biased. Accepting that we may be biased is the first step to explore and formulate new strategies for better decision-making.

As Annie Duke says in her book Thinking In Bets

Our narrative of being a knowledgeable, educated, intelligent person who holds quality opinions isn’t compromised when we use new information to calibrate our beliefs, compared with having to make a full-on reversal. This shifts us away from treating information that disagrees with us as a threat, as something we have to defend against, making us better able to truth seek

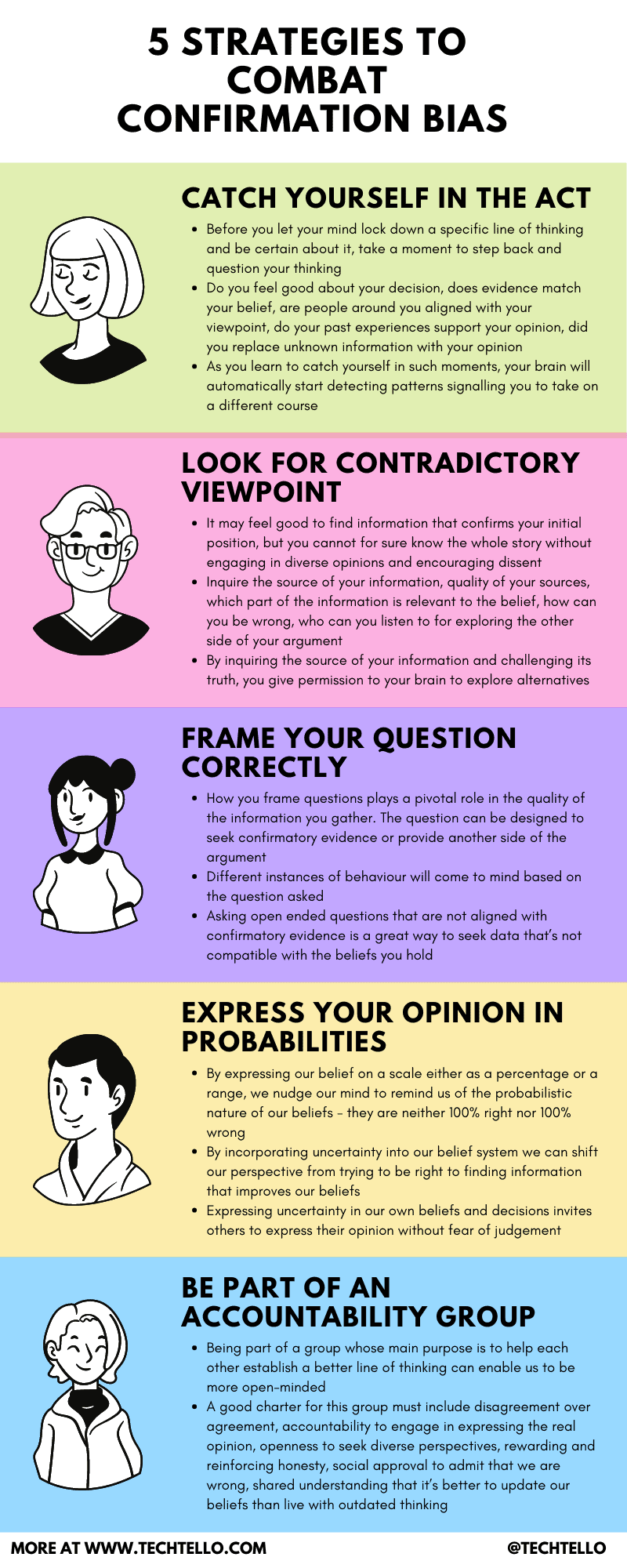

Follow these 5 strategies to combat confirmation bias during decision making:

1. Catch yourself in the act

Before you let your mind lock down a specific line of thinking and be certain about it, take a moment to step back and ask yourself these questions:

- Do you feel good about your decision

- Does evidence match your belief

- Are people around you aligned with your viewpoint

- Do your past experiences support your opinion

- Did you replace incomplete or unknown information with your opinion

Without hearing diverse opinions, the certainty of the decision may feel good in your body, but without challenging your thinking, validating your assumptions and an attempt to apply an inversion mental model to shift from “I’m right” to “I may be wrong”, your thinking will be limited by your own view of the world.

As you learn to catch yourself in such moments, your brain will automatically start detecting patterns signalling you to take on a different course.

2. Look for contradictory viewpoint

It may feel good to be right and find information that confirms your initial position, but you cannot for sure know the whole story without engaging in diverse opinions and encouraging dissent to uncover alternate viewpoints. Before you open yourself to other possibilities, ask yourself these questions:

- What is the source of my information

- What is the quality of my sources and how much do I trust them

- Which part of the information is relevant to the belief

- How can I be wrong

- Who can I listen to for exploring the other side of my argument

- How can I see information beyond my circle of competence

- What barriers do I have that limits me to explore more possibilities and how can I get rid of them

By inquiring the source of your information and challenging its truth, you give permission to your brain to explore alternatives.

3. Frame your question correctly

How you frame questions plays a pivotal role in the quality of the information you gather. The question can be designed to seek confirmatory evidence or provide another side of the argument.

It’s best understood using an example. Let’s say you have decided to quit your job as you find your boss biased and unsupportive of your learning and growth. You have all the evidence that you have rationalised ample times in your head.

When seeking advice from others in your team, you may ask

“Is our boss biased”

vs

“What information says that our boss is unbiased”

The information that comes to mind is based on the question you ask. The different instances of your boss behaviour will come to mind when looking for information that confirms his biased behaviour vs unbiased behaviour.

Asking open ended questions that are not aligned with confirmatory evidence is a great way to seek data that’s not compatible with the beliefs you hold.

4. Express your opinion in probabilities

By expressing our belief on a scale either as a percentage or a range, we nudge our mind to remind us of the probabilistic nature of our beliefs – they are neither 100% right nor 100% wrong.

Saying “I am 70% confident that we should go with this option” is very different from stating “we should go with this option”.

By incorporating uncertainty into our belief system we can shift our perspective from trying to be right to finding information that improves our beliefs. It creates open-mindedness to accept new information that does not align with our viewpoint as any new information can act as a catalyst for better thinking and can help in adjusting our original thoughts to align with a new reality.

It also invites others to share their perspective as stating something as probabilistic gives them the confidence that you are more open to exploring the real truth. Stating your opinion as 100% right or others as 100% wrong, prevents others from collaborating on ideas. Either they are scared their ideas might be ridiculed or they will end up hurting or damaging the relationship by saying “you’re wrong”.

Expressing uncertainty in our own beliefs and decisions invites others to express their opinion without fear of judgement or reprisal. It shifts the focus of the conversation from “I’m right” and “you’re wrong” to “Let’s work together to learn something new”.

Annie Duke beautifully sums this up in her book Thinking In Bets

When we work toward belief calibration, we become less judgmental of ourselves. Incorporating percentages or ranges of alternatives into the expression of our beliefs means that our personal narrative no longer hinges on whether we were wrong or right but on how well we incorporate new information to adjust the estimate of how accurate our beliefs are. There is no sin in finding out there is evidence that contradicts what we believe. The only sin is in not using that evidence as objectively as possible to refine that belief going forward

5. Be part of an accountability group

The way we are wired to think and act as human beings, we sometimes cannot see what others can see so clearly.

Being part of a group whose main purpose is to help each other establish a better line of thinking can enable us to be more open-minded and evaluate our own thoughts deeply before being fixated to a specific opinion.

By establishing a charter upfront, we can hold each other accountable to it and make it difficult for us to drift to our natural mode of confirmatory thinking and bias. A good charter for this group must include

- Disagreement over agreement

- Accountability to engage in expressing the real opinion

- Openness to seek diverse perspectives

- Rewarding and reinforcing honesty

- Social approval to admit that we are wrong

- Shared understanding that it’s better to update our beliefs than live with outdated thinking

Our confirmatory bias will make us naturally incline towards people just like us or who will agree with what we have to say. To make this setup successful, an important element is to find people from diverse backgrounds and thinking who agree to this charter and will hold others accountable to it.

Recommended Reading

Examples of confirmation bias

While this bias is all around us as we continue to live our daily lives, it may be hard to spot. These few examples will help you understand this bias better.

Confirmation bias in business

Enron corporation was the largest business scandal in American history. The company started in 1985 and was named America’s most innovative company for 6 years before going bankrupt in 2001.

It was a carefully crafted accounting fraud that hid billions of dollars in debt from failed deals and projects.

People saw what they wanted to believe about Enron and ignored all hints that pointed something sketchy in the way they operated. It was confirmation bias that allowed Enron’s leadership to fool regulators with fake holdings and off-the-books accounting practices.

This article Is Enron overpriced by Bethany McLean triggered some great questions that lead to its downfall in 2001.

Confirmation bias in travel plans

Let’s consider that you have planned your long pending vacation this summer and booked your flight, hotel and sightseeing to make the most of your trip. Just a week before your vacation, you hear about heavy rains in certain places you intend to visit.

With your mind pushing you to find positive information to make this trip at all costs, you will look for all evidence that will support your internal desire to travel. Instead of being directed towards information that explains why it’s a bad time to travel, you will end up digging data that states why it’s not so bad after all.

You may even rationalise that it’s just rain and in some of your previous travels, unintended rain actually made the experience more fun.

Confirmation bias in this scenario may make you disregard all important data that suggests it’s wise to delay the trip. With your belief system telling you that it’s just rain and nothing bad can ever happen, you may end up taking the trip only to realise later that it was a pretty bad decision.

Confirmation bias in making a promotion decision

You have a really smart tech lead on your team with the right technical chops, great problem-solving skills and product aptitude. He seems to fit your mental model of the best person to become a manager.

Feedback from other people in the team may point out that he’s not very collaborative, does not communicate well or is being rude to people who don’t know things as well as he does.

However, your strong opinion about him may make you ignore all hints that point to this feedback. With your belief system telling you that he will be a great manager, you may end up ignoring all evidence that counteracts it.

Confirmation bias will prevent you from seeing the reality of the situation and you may end up making a disastrous decision that pushes the team into a storming team development stage.

While we all have many other biases, confirmation bias is the most profound of all in how it dictates a large part of our decisions. Unless we learn to recognise, acknowledge and act on it, we will continue to be driven by these biases without an opportunity to see the numerous possibilities that lie ahead.

I hope you will make an effort to find confirmation bias within you. If you have some great strategies that have worked personally for you in combating this bias, I would love to hear about them. Write to me or drop your thoughts in the comments below.