Availability Heuristic: Trade-Off Between Efficiency And Accuracy In Decision Process

There are specific moments that register in our minds and sit at the forefront of our decision making process and others that simply go unnoticed as they do not demand our attention and take up a back seat in our memory lane.

Events that evoke strong emotional response tend to stick more – negative experience of working with a coworker, positive feelings of being appreciated by our manager, a great advertisement that connects with our principles and values, fear of being rejected by an interviewer and the joy of seeing our idea come to life.

The recency of these events and the emotional response that they generate influence our decisions in a huge way. When looking for information to guide our decisions, we rely on instances that come readily to mind without validating the specific content, their relevance and even their probability of occurrence.

We exaggerate the probability of an event simply by the ease with which its examples come to mind. This specific bias known as availability heuristic is deeply entrenched within the human operating system.

As Dan Ariely puts it in Predictably Irrational “Standard economics assumes that we are rational. But, we are far less rational in our decision making. Our irrational behaviors are neither random nor senseless – they are systematic and predictable. We all make the same types of mistakes over and over, because of the basic wiring of our brains”

A CEO with multiple successes in the past may find it difficult to recall instances of failure. Availability heuristic is at play when difficulty in retrieving failure scenarios can make him overconfident in his current venture and invest in sunk costs while ignoring opportunity costs.

A manager may treat a mistake from her team member as a sign of their incompetence based on a similar instance that happened recently. If the areas in which her team member does well is not immediately visible and doesn’t show up when she recalls past information, availability bias can make her form an inaccurate judgment about her team member.

A marketer may decide against a social media channel for her marketing campaign simply on the basis of her last failure which is top of her mind while conveniently ignoring other successful stories from the past.

This tendency to treat heuristics as facts, basing decisions on what comes readily to mind and what’s most recent as opposed to what’s more accurate leads to workplace discrimination, poor decisions, inaccurate perceptions and bad judgments.

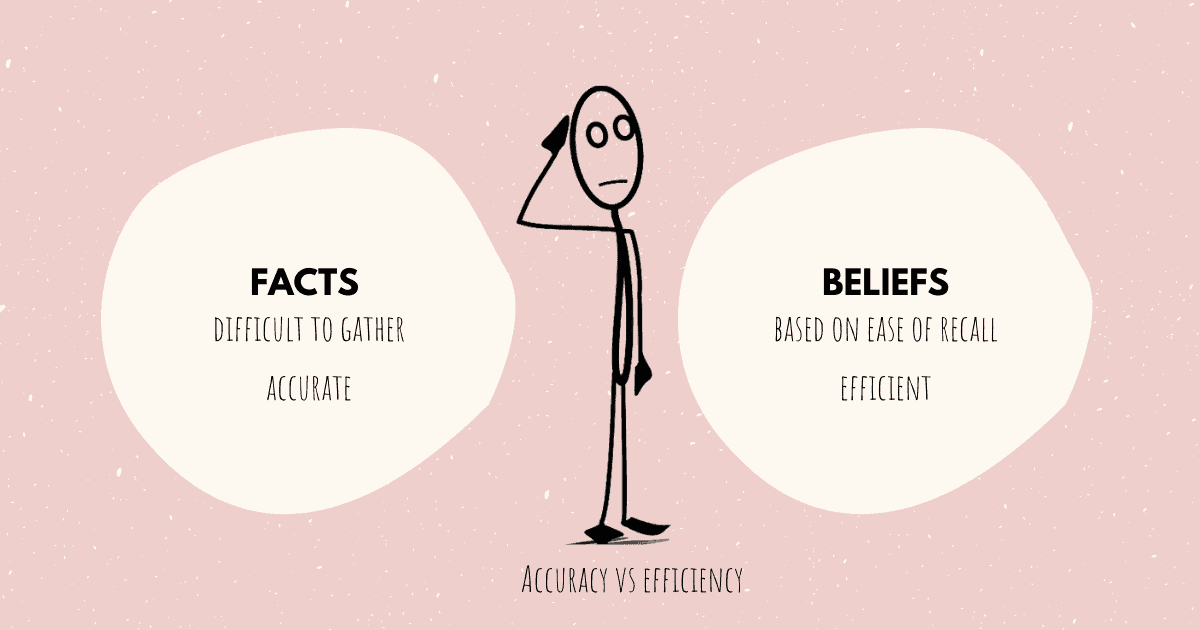

Efficiency vs Accuracy: How availability heuristic impacts decisions

Our brain’s ability to fetch a specific piece of information from large amounts of data that we consume on a regular basis is definitely efficient and it serves us well most of the time when making decisions that do not impact us and others in a huge way.

But using this data when deciding on the likelihood of something happening again or determining how the future would turn out may be far from accurate.

Learning when we can rely on efficiency and when we need to be accurate can help us in making better decisions.

Before we learn to take control of this bias, let’s understand how and when availability heuristic shows up. This is how our brain optimises for efficiency –

1. Using shortcuts

When forecasting future outcomes or determining the probability of certain events, our brain applies mental shortcuts in an attempt to find the relevant information.

These shortcuts are optimised for speed of retrieval as opposed to the correctness of the data.

“We need shortcuts, but they come at a cost. Many decision-making missteps originate from the pressure on the reflexive system to do its job fast and automatically. No one wakes up in the morning and says, “I want to be closed-minded and dismissive of others.” But what happens when we’re focused on work and a fluff-headed coworker approaches? Our brain is already using body language and curt responses to get rid of them without flouting conventions of politeness. We don’t deliberate over this; we just do it. What if they had a useful piece of information to share? We’ve tuned them out, cut them short, and are predisposed to dismiss anything we do pick up that varies from what we already know”, says Annie Duke in Thinking In Bets.

It’s these shortcuts that give way to availability heuristic and make us label people as this is who they are without taking their situational factors into account, reject ideas, fear conflicts and imagine the worst possibilities that don’t even exist.

Cognitive Distortions Bundle

Challenge and replace irrational thoughts with more realistic and adaptive thoughts.

2. Ease of recall

Ease of recall substitutes for rational thought. Something that comes readily to mind is given a higher weightage. We assume that just because we are able to recall it easily, it must be highly probable.

By relying only on ease of retrieval, we may ignore other instances that are better suited to make a decision but require deliberate thinking to dig deeper and analyse closely.

When thinking about a team member’s performance, a manager may take only their recent performance into account since it’s easy to recall while ignoring all their valuable contribution in the months preceding it. Being at the effect of availability heuristic, they will rate their team member incorrectly.

When deciding who to trust on a key project, a leader may be quick to consider an engineer who recently delivered a project on time while ignoring everyone else who is equally capable but just not visible to them as much.

Daniel Kahneman also points this out in Thinking, Fast And Slow “The same bias contributes to the common observation that many members of a collaborative team feel they have done more than their share and also feel that the others are not adequately grateful for their individual contributions”

This happens because it’s easy for us to recall our own contributions while it’s hard to remember this data for other team members.

Ease of retrieval is a bad predictor for judging the frequency or probability of an event and using that information to make decisions.

3. Events that leave a lasting impression

Our brain’s capacity to process information is limited. When exposed to large amounts of data every day, our brain picks and chooses certain events that leave a lasting impression in our minds while ignoring others. This limitation results in filtering a large amount of valuable data and presenting only a subset during the decision making process.

What catches our attention depends on whether we choose to focus on a specific piece of information, what appeals to our senses, our past experiences, upbringing and many other factors.

“The attention which we lend to an experience is proportional to its vivid or interesting character; and it is a notorious fact that what interests us most vividly at the time is, other things equal, what we remember best”, says William James in The Principles Of Psychology.

Advertisement companies try to tap into this limitation by creating a powerful narrative that has a much higher likelihood of leaving a lasting impression on our minds.

When making important decisions, basing our judgment on this limited set of data can be highly inaccurate.

4. Applying substitution

“The availability heuristic, like other heuristics of judgment, substitutes one question for another: you wish to estimate the size of a category or the frequency of an event, but you report an impression of the ease with which instances come to mind. Substitution of questions inevitably produces systematic errors”, says Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast And Slow.

When looking for information, our brain substitutes one question for another based on what comes to mind. We do not even realise that the information we are seeking is not an answer to the original question, but rather a snapshot of what comes conveniently to mind.

When thinking about “What’s the likelihood of meeting my delivery timeline”, you may substitute it with “Did I deliver my last project on time.” Using the last project to decide how the current one will turn out is a case of poor substitution.

Availability bias is an integral part of being human and plays a crucial role in helping us act fast. Being deliberate in all our decisions will be highly ineffective and will slow us down. It will also lead to decision fatigue by spending mental resources on inconsequential decisions while leaving less energy for making critical decisions.

Instead of trying to get rid of availability heuristic, let’s learn to recognise situations in which stakes are high and shift from letting our brain run on autopilot to taking control for digging deeper and discovering hidden alternate reality.

Managing availability heuristic for making better decisions

Self awareness is the first step to any form of transformation. Without accepting the existence of availability bias, any strategies that you try to put in place to counteract it will be futile.

Stephen R. Covey describes in The 7 Habits Of Highly Effective People “Self-awareness enables us to stand apart and examine even the way we “see” ourselves—our self-paradigm, the most fundamental paradigm of effectiveness. It affects not only our attitudes and behaviors, but also how we see other people. It becomes our map of the basic nature of mankind”

By acknowledging that you are at the effect of this bias much like others, you can give permission to your brain to implement these 3 strategies for making better decisions –

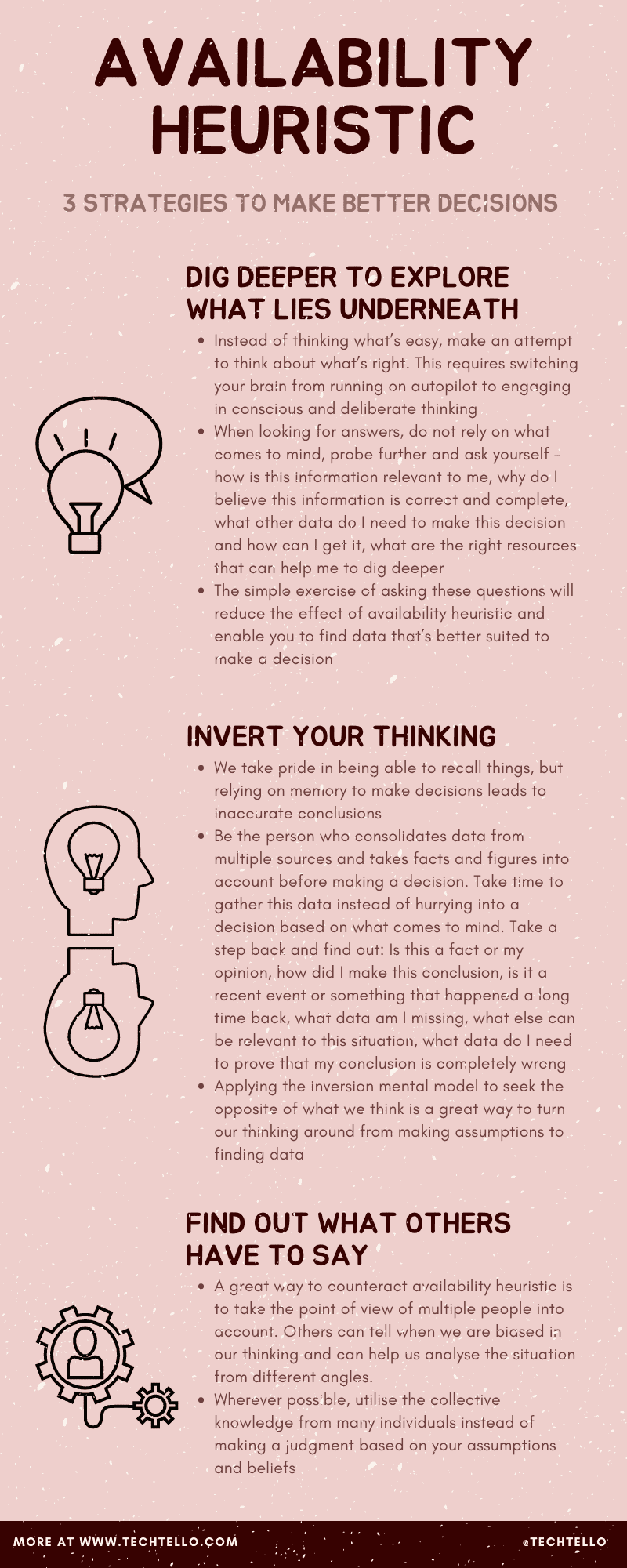

1. Dig deeper to explore what lies underneath

Instead of thinking what’s easy, make an attempt to think about what’s right. This requires switching your brain from running on autopilot to engaging in conscious and deliberate thinking.

When looking for answers, do not rely on what comes to mind, probe further and ask yourself some of these questions:

- How is this information relevant to me

- Why do I believe this information is correct and complete

- What other data do I need to make this decision and how can I get it

- What are the right resources that can help me to dig deeper

- How can I avoid confirmation bias that can make me ignore contradictory data points

The simple exercise of asking these questions will reduce the effect of availability heuristic and enable you to find data that’s better suited to make a decision.

2. Invert your thinking

We take pride in being able to recall things, but as we learned earlier relying on memory to make decisions leads to inaccurate conclusions.

Be the person who consolidates data from multiple sources and takes facts and figures into account before making a decision. Take time to gather this data instead of hurrying into a decision based on what comes to mind. Take a step back and find out –

- Is this a fact or my opinion. How did I make this conclusion

- Is it a recent event or something that happened a long time back. What data am I missing

- What else can be relevant to this situation

- What do other data points teach me about this scenario

- What data do I need to prove that my conclusion is completely wrong

Applying the inversion mental model to seek the opposite of what we think is a great way to turn our thinking around from making assumptions to finding data.

3. Find out what others have to say

Daniel Kahneman advises in Thinking, Fast And Slow “As we navigate our lives, we normally allow ourselves to be guided by impressions and feelings, and the confidence we have in our intuitive beliefs and preferences is usually justified. But not always. We are often confident even when we are wrong, and an objective observer is more likely to detect our errors than we are”

A great way to counteract availability heuristic is to take point of view of multiple people into account. Others can tell when we are biased in our thinking and can help us analyse the situation from different angles.

Wherever possible, utilise the collective knowledge from many individuals instead of making a judgment based on your assumptions and beliefs.

Availability heuristic examples

Let us consider these examples to understand availability heuristic better.

Tversky and Kahneman experiment

Taken from Wikipedia –

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two prominent psychologists began work on a series of papers examining “heuristic and biases” used in the judgment under uncertainty. Prior to that, the predominant view in the field of human judgment was that humans are rational actors. Kahneman and Tversky explained that judgment under uncertainty often relies on a limited number of simplifying heuristics rather than extensive algorithmic processing.

Tversky and Kahneman argued that the number of examples recalled from memory is used to infer the frequency with which such instances occur.

In an experiment to test this explanation, participants listened to lists of names containing either 19 famous women and 20 less famous men or 19 famous men and 20 less famous women. Subsequently, some participants were asked to recall as many names as possible whereas others were asked to estimate whether male or female names were more frequent on the list. The names of the famous celebrities were recalled more frequently compared to those of the less famous celebrities. The majority of the participants incorrectly judged that the gender associated with more famous names had been presented more often than the gender associated with less famous names.

Tversky and Kahneman argue that although the availability heuristic is an effective strategy in many situations, when judging probability, use of this heuristic can lead to predictable patterns of errors.

Deciding on a promotion

A manager under the effect of availability bias may decide to not promote a team member based on the outcome of their most recent deliverable.

The recency bias along with ease of recall will add more weight to what happened recently as opposed to equally considering their past performance. Small mistakes during an appraisal cycle can cost someone their promotion.

This breaks trust in organisations, obstructs innovation and makes people extra cautious during the performance appraisal season.

Customer’s experience

An otherwise happy customer with hundreds of perfectly delivered orders may choose to focus on one bad experience under the effect of availability heuristic when filling out a customer feedback form.

Without taking the entire dataset into account, their biased feedback towards that one order will not reflect their actual sense of satisfaction with the service.

The same applies when designing for customer experience. A small glitch in the app on the last touchpoint in a customer’s ordering journey may screw up the fantastic experience that they felt all along.

When managing and designing for customer’s experience, availability bias plays a critical role.

While making decisions, find the right trade-off between efficiency and accuracy by taking availability heuristic into account when the stakes are high. It requires digging deeper instead of falling for what comes intuitively to mind, forcing ourselves to invert our thinking, seek data that challenges our point of view and using collective knowledge from others to look beyond our beliefs and assumptions.

What instances come to mind? Write to me or share your comments below on how you see this bias play out in your work and life.