Sunk Cost Fallacy: Know When You Need To Pull The Plug

Basing our decision on what’s going to happen in the future and not what investments have been made in the past by treating every decision as a new one is indeed very difficult. It’s not a clear, straightforward choice.

The more our past investment, the harder it is to abandon it. Without realising what we have invested is already gone, we are not able to shift our mental frame from the “cost of moving on” to the “cost of not moving on.”

Sunk cost fallacy causes us to ignore the promise of a better experience in the future by making an attempt to negate a loss in the past. In other words, our past investments over influence our current decisions.

“Humans are bedeviled by the “sunk cost fallacy.” Having invested time or money in something, we are loath to leave it, because that would mean we had wasted our time or money, even though it is already gone”, says David Epstein in Range.

A new technological innovation can make many products unviable, but how many companies decide to forgo the past investments that impact their products in a huge way by considering future demands?

How easy is it for someone to give up on a career that makes them miserable after spending years trying to hone their skills in a particular field?

Is it a simple choice to kill a project after spending months, a decent amount of money and a fair amount of personal time and effort once it fails to generate the desired impact?

Do you find it easy to let go of a toxic employee after investing huge amount of resources during the hiring process and more time and energy to help them improve?

These may look like rational choices on the surface. But, as a species, we are not driven by rationality.

Warren Buffet said, “The most important thing to do if you find yourself in a hole is to stop digging.” But following this advice is not easy. Since the investment is not just financial, but an emotional one as well, the decision to pull the plug is indeed very painful.

The cognitive dissonance that arises from investing and not getting expected returns leads to a psychological trap. Sunk costs, invested time, money and effort that is now irrecoverable and no longer relevant to current decision impacts our thinking in a huge way.

We fail to ask:

- Am I thinking forward or holding onto the past?

- What’s the opportunity cost to continue further?

- Will further investment fix the situation or cause greater loss?

Why sunk cost bias is so pervasive

From small everyday decisions to big ones, sunk cost bias is all around us. It’s so deeply embedded in our thinking process that we may not even realise it.

To weaken the effect of sunk cost bias, we first need to learn why we take sunk costs into account when making rational decisions.

1. Avoiding pain over gain

Daniel Kahneman, psychologist and economist notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making explains in Thinking, Fast And Slow how loss aversion guides our decision making –

“Many of the options we face in life are mixed: there is a risk of loss and an opportunity for gain, and we must decide whether to accept the gamble or reject it. For most people, the fear of losing $100 is more intense than the hope of gaining $150. People are loss averse and losses loom larger than gains”

He also writes –

“The disadvantages of a change loom larger than its advantages, including a bias that favors the status quo. Loss aversion does not imply that you never prefer to change your situation; the benefits of an opportunity may exceed even over-weighted losses. Loss aversion implies only that choices are strongly biased in favor of the reference situation and generally biased to favor small rather than large changes”

Since we respond more strongly to losses than to gains, giving up something we are invested in is more painful than the pleasure of getting an equal amount of value.

Loss aversion tricks our mind into bearing the incremental cost of continuing as opposed to taking the hard decision of parting with our investment.

It makes us turn down favourable opportunities right in front of us by not being able to forgo the past value we attached to a decision.

Cognitive Distortions Bundle

Challenge and replace irrational thoughts with more realistic and adaptive thoughts.

2. Belief that quitting is for losers

Persistence despite failures is considered a sign of leadership and quitting, well the opposite of it. Leadership seems to have become synonymous with persistence even when it doesn’t make sense.

Vince Lombardi, an American football coach popularised “Winners never quit and quitters never win”. All this advice that “quitting is for losers” and “persevere despite failures” can hit us hard if we fail to recognise when this advice is valid – are you quitting too soon, are you scared of failures, to when you are simply in it to protect your decision.

“Winners quit fast, quit often, and quit without guilt”, says Seth Godin in The Dip and David Epstein writes in Range “No one in their right mind would argue that passion and perseverance are unimportant, or that a bad day is a cue to quit. But the idea that a change of interest, or a recalibration of focus, is an imperfection and competitive disadvantage leads to a simple, one-size-fits-all Tiger story: pick and stick, as soon as possible”

The belief that quitting is for losers can strengthen our emotional connection with our past decision and prevent us from seeing beyond our sunk cost.

Done at the right time, quitting can be the most beautiful thing that can help us move forward, define our own path, get past our fear of failures and make the right choices without feeling intimidated.

3. Notion that admitting mistake hurts reputation

To free ourselves of our past decisions and look forward, we need to admit mistakes – first to ourselves and then to others.

Admitting a mistake is not so easy. Accepting that we made a bad decision requires getting past the feeling of shame and worrying about protecting our image to invest in doing what’s right.

Stephen R. Covey explains in The 7 Habits Of Highly Effective People

You feel terribly guilty if you make a mistake because you “remember” deep inside the emotional scripting when you were very vulnerable and tender and dependent. You “remember” the emotional punishment, the rejection, the comparison with somebody else when you didn’t perform as well as expected

There’s social pressure to stick to our past decisions with the fear of looking incompetent. It can make us justify our past decision by making further investment in an already sunk cost as opposed to accepting a personal failure.

4. Past successes delude future investments

Early success can make us blind to future failures. Our perseverance and hard work may have paid off earlier but every situation is different and must be viewed through a unique lens.

Initial rewards can reinforce our belief in our idea and prevent us from noticing when those rewards disappear and our idea starts showing signs of a downward spiral.

Instead of reassessing our initial vision as things get harder and uncertain, we stick to our decision. We think “if it worked out earlier, it must work out this time too.”

In effect, our past successes can mislead us to invest incrementally in our sunk costs and ignore opportunity costs.

5. At the effect of information bias

When things do not work out as intended, we look for information that supports our belief system and disregard anything that contradicts our point of view.

David McRaney writes in You Are Not So Smart –

When you need something to be true, you will look for patterns; you connect the dots like the stars of a constellation. Your brain abhors disorder. You see faces in clouds and demons in bonfires. Those who claim the powers of divination hijack these natural human tendencies. They know they can depend on you to use subjective validation in the moment and confirmation bias afterward

Confirmation bias can prevent us from seeing the reality of our situation and push us down a path that must have been abandoned long ago. It can make us give more fuel to our sunk costs instead of objectively looking into the future.

6. Emotional connection over a rational one

Our two strong emotions regret and blame are at the center of our decision-making process. The regret of not trying hard enough and blaming ourselves for quitting too soon or regret of continuing long past our failures and blaming ourselves for not seeing it sooner.

As Maria Konnikova says in The Confidence Game “It wasn’t about letting go of what you had. It was about letting go of the chance of winning and having to live with the regret.”

When we draw from our past experiences to make sense of our current situation, these emotions can wreak havoc on our rationality in the moment. It can either make us quit too soon or continue despite any signs of improvement.

Trapped by the commitment we made earlier and lack of a fresh perspective can cause us to have an emotional connection with our decision as opposed to a rational one.

7. False sense of hope

There’s indeed a fine line between commitment and over-commitment to an idea. It’s often not visible when we cross this line.

Even a slight hope that we can turn things around can push us way past a sensible investment on our decisions.

Instead of asking – “why should I continue”, “what’s the opportunity cost involved in continuing on this decision”, the hope that we can recover our sunk costs makes us ask the wrong questions – “what should I do to fix it”, “how should I go about doing it?”

What does it take to avoid sunk cost bias and refocus effort

Peter Drucker shares his wisdom in The Five Most Important Questions

To abandon anything is always bitterly resisted. People in any organization are always attached to the obsolete—the things that should have worked but did not, the things that once were productive and no longer are. Abandoning anything is thus difficult, but only for a fairly short spell. Rebirth can begin once the dead are buried; six months later, everybody wonders, “Why did it take us so long?”

So let’s learn to disconnect from the emotion of our sunk costs, accept vulnerability and make that hard call.

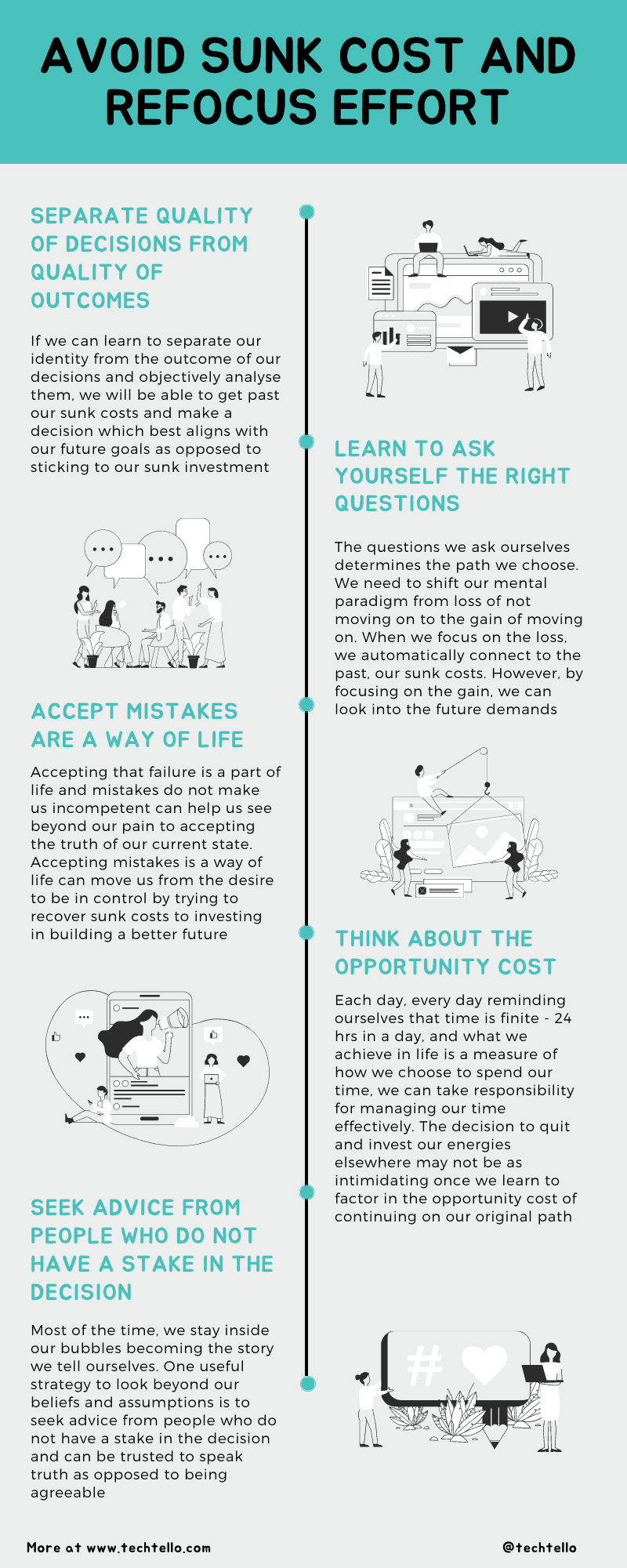

1. Separate quality of decisions from quality of outcomes

Annie Duke, a professional poker player explains how to separate decisions from outcomes in Thinking In Bets “The world is structured to give us lots of opportunities to feel bad about being wrong if we want to measure ourselves by outcomes. Don’t fall for it! Redefining wrong allows us to let go of all the anguish that comes from getting a bad result. But it also means we must redefine “right.” If we aren’t wrong just because things didn’t work out, then we aren’t right just because things turned out well”

We think our decisions define us. This emotional connection with our decision can make us invest in new strategies and tactics, try harder and continue to push forward on a failed cause even when all signs point in the other direction.

If we can learn to separate our identity from the outcome of our decisions and objectively analyse them, we will be able to get past our sunk costs and make a decision which best aligns with our future goals as opposed to sticking to our sunk investment.

2. Learn to ask yourself the right questions

The questions we ask ourselves determines the path we choose. We need to shift our mental paradigm from loss of not moving on to the gain of moving on.

When we focus on the loss, we automatically connect to the past, our sunk costs. However, by focusing on the gain, we can look into the future demands. It’s a subtle shift, but indeed a very powerful one to move from a negative mental frame to a positive one.

Asking great open ended questions to ourselves in such critical moments can guide us to ignore sunk investments and make a truly rational decision –

- What factors did I take into account when making the decision and how are those initial assumptions holding good in the current scenario. How are these assumptions valid in the future?

- What has changed since I started and how does my current direction align with what I want to achieve in the future. What have I done to stay in touch with outside reality?

- How do I know if I am putting in the right solution to the problem. Am I still building what I originally envisioned or is it something people need now?

- What’s the basis of my decision based on the state of my mind – fearful of failing and trying to avoid pain or in touch with the reality of my situation?

- If I weren’t invested in this decision yet, would I be willing to enter it today?

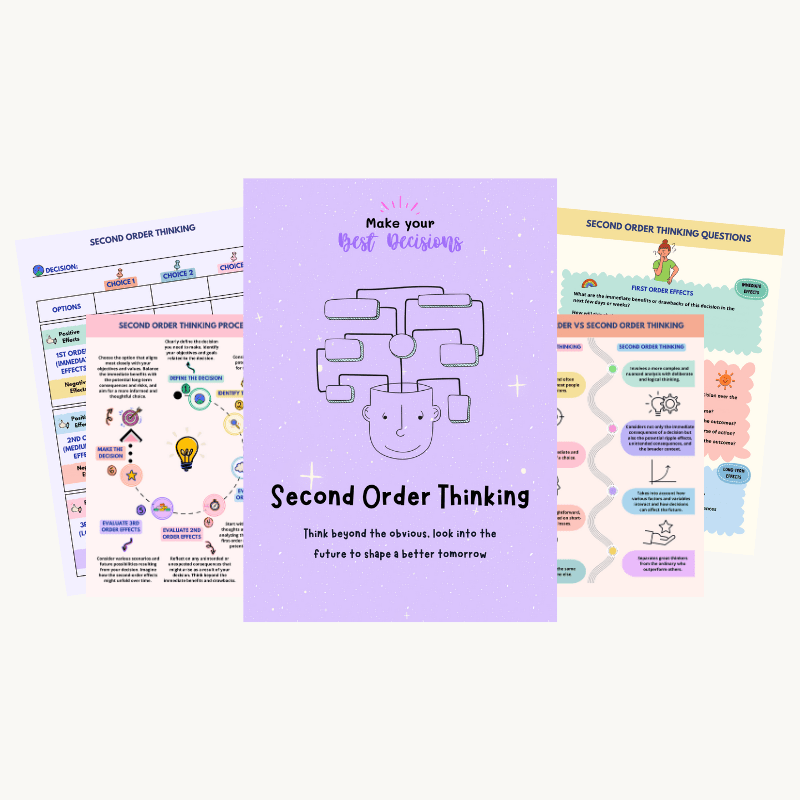

- What are the second-order consequences of my decision?

3. Accept mistakes are a way of life

David McRaney says in You Are Not So Smart

“You make plans and decisions assuming randomness and chaos are for chumps. The illusion of control is a peculiar thing because it often leads to high self-esteem and a belief your destiny is yours for the making more than it really is. This over-optimistic view can translate into actual action, rolling with the punches and moving ahead no matter what. Often, this attitude helps lead to success. Eventually, though, most people get punched in the stomach by life”

He also adds –

“Remember most of the future is unforeseeable. Learn to coexist with chaos. Factor it into your plans. Accept that failure is always a possibility, even if you are one of the good guys; those who believe failure is not an option never plan for it. Some things are predictable and manageable, but the farther away in time an event occurs, the less power you have over it. The farther away from your body and the more people involved, the less agency you wield. Like a billion rolls of a trillion dice, the factors at play are too complex, too random to truly manage. You can no more predict the course of your life than you could the shape of a cloud. So seek to control the small things, the things that matter, and let them pile up into a heap of happiness. In the bigger picture, control is an illusion anyway”

Accepting that failure is a part of life and mistakes do not make us incompetent can help us see beyond our pain to accepting the truth of our current state.

Ask yourself –

- What does this mistake teach me about myself

- How can I adopt a growth mindset as opposed to a fixed mindset

- What learnings can I apply from this decision to my future choices

- How can I factor unknowns and failures in my future planning

- How can I spend my mental energy in improving things that are within my control as opposed to wasting time in those that are outside my circle of influence

Accepting mistakes is a way of life can move us from the desire to be in control by trying to recover sunk costs to investing in building a better future.

4. Think about the opportunity cost

Each day, every day reminding ourselves that time is finite – 24 hrs in a day, and what we achieve in life is a measure of how we choose to spend our time, we can take responsibility for managing our time effectively.

The decision to quit and invest our energies elsewhere may not be as intimidating once we learn to factor in the opportunity cost of continuing on our original path.

Putting it into practice requires –

- Periodic comparison of our original goals to future possibilities

- Evaluating the opportunity cost of continuing on the current path – what else can you do if you decide to quit?

- Expected gain from current investments as opposed to the cost of delaying a new project

5. Seek advice from people who do not have a stake in the decision

Most of the time, we stay inside our bubbles becoming the story we tell ourselves. We do not see where things are headed while others outside can clearly see it.

Looking outside this bubble is not possible unless we acknowledge that we live inside one. Once we can train our mind to be aware of our inherent biases, we can take steps to see beyond them.

One useful strategy to look beyond our beliefs and assumptions is to seek advice from people who do not have a stake in the decision and can be trusted to speak truth as opposed to being agreeable.

Having an accountability group where rules of the group are set upfront can be very helpful in seeing past our version of the reality.

Examples of sunk cost fallacy

Consider these examples of sunk cost fallacy to catch them in action when they play out in your life both at work and in relationships –

- Continuing to watch a Netflix series all the way till the end though you stopped enjoying at Season 2

- Investing in platform re-architecture even after you stopped believing in its actual value

- Shipping a product feature to the market even though the change in market conditions makes the feature useless

- Sticking to a career choice you made early on even though it makes you miserable

- Not giving up on a relationship after spending years trying to make it work though nothing seems to work

- Finishing up the last spoon of ice cream even though you were full halfway through it

- Trying to turn around a project only to prove you were right though you know that it has failed long back

- Refusing to accept a mistake and change gears with the belief that it will make you look incompetent

Sunk cost bias is a part of being human, believing we are rational even when we are not, refusing to acknowledge a large part of our decisions are biased and what we see as reality is just a frame of reference from which we see the world and things in it.

Knowing when it’s wise to stick and when it’s time to quit is indeed a very difficult choice. It requires mastering the balance between the decisions of the past, opportunities of today to the possibilities of tomorrow.

Achieving a perfect amalgamation of past, present and future is not possible, but we can learn to make it better. How do you see sunk cost bias play out in your work and life? Write to me or share your thoughts in the comments below.